A South African farmer’s focus on happy cows

Happy cows are the most profitable, believes Jan Grey, dairy farmer in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Management systems that maximise cow comfort therefore form a pivotal part of maintaining a sustainable operation in an increasingly difficult market.

The Mpumalanga region of eastern South Africa was once the dairy hub of the country, but as profitability in this industry dwindled, dairy farms have become fewer, but bigger. Jan Grey himself was faced with the decision 4 years ago to ‘go big or go home’. Opting to capitalise on economies of scale, he doubled the size of his facilities.

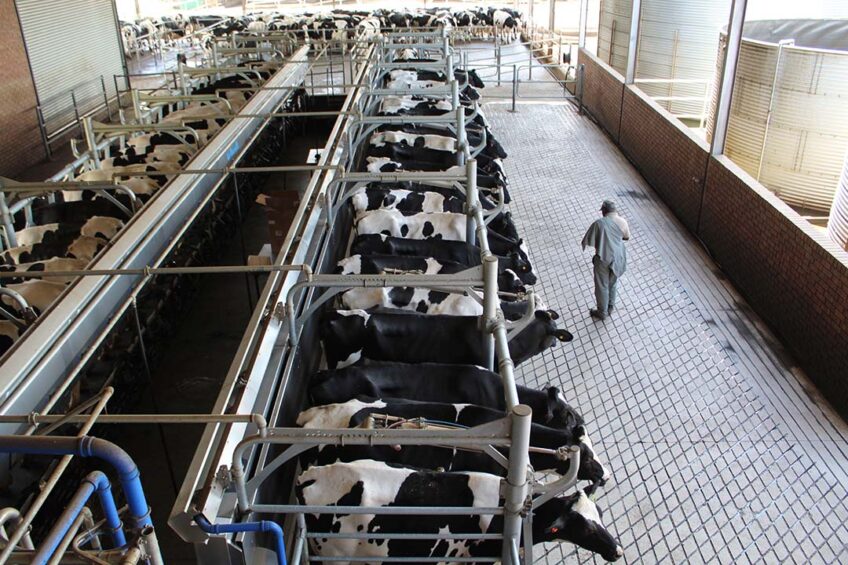

Today, the farm stocks 1,271 Holstein cows of which between 550 and 700 are in milk at any given time. Grey’s goal is to reach 900 cows in milk, to make maximum use of the newly-installed Delaval 50-point rapid exit milking system. This investment has been a key element of the cow comfort philosophy, since cows are able to leave the milking parlour as soon as they are milked. “No one has to chase them, and they can get back to eating and lying down much quicker than before. Cows are not unlike humans in that they don’t want to spend all day on their feet,” explains Grey.

Input and output

Janvos Landgoed is a total mixed ration (TMR) farm, with most of the feed grown on site. Production is therefore uninterrupted year-round. Although TMR farmers are in the minority in South Africa – making up only 25% of all dairy farms – they supply the majority of milk.

The ration is silage-based, consisting of maize, eragrostis, high protein concentrate, brewer’s yeast and molasses.

The 350 hectares of maize lands produce between 8,000 tonnes and 14,000 tonnes of silage annually. Both the maize and eragrostis are mostly dryland, dependent on the 690 mm of annual rain. Manure slurry from the dairy is spread on the fields, and fertiliser added according to measured nutrient deficiencies.

Heifers are kept in kikuyu grass camps from the time they have left the calving camps until they go into production. Here they also receive a mixed ration. Stocked at a rate of 4 cows per hectare, the camps serve more to allow for sun and fresh air than pasture grazing. Grey believes that this is important to boost their well-being before going into production.

For this reason, pregnant heifers and far-off dry cows are also kept in outside camps. Far-offs spend 40 days here which Grey says is necessary to allow the cow to rest, rejuvenate and thereby maximise lifetime production.

The herd achieves an average of 12,539 litres per cow per lactation, with cows averaging 1.9 lactations each. Grey admits that this number is low since a large percentage of the herd consists of heifers, as he is in the process of growing his herd. Improving the number of lactations is also being focused on through better genetic selection. Cows are mostly artificially inseminated using sexed semen, to allow for maximum heifers and minimum bull-calves.

Happy campers – investing in cow comfort

A key investment in cow comfort has been the roof that has been erected over the waiting area of the parlour. “February and March are the worst times of the year to milk. Maximum temperatures can reach up to 35°C, and the ample rain can cause mud fever. Temperatures under the roof are, however, 11°C cooler and being protected from the rain means cows are generally more comfortable. The proof is in the milk since production has increased as a result, with the cows averaging 38.36 litres each, which is phenomenal for this time of year,” says Grey.

The free stalling system has sand bedding on the floor, which is topped up weekly, providing a hygienic, soft area to lie on. “It’s expensive, but it increases the cows’ comfort,” says Grey.

The cow comfort system entails railings that give way when cows lie against them, mounted brushes so cows can scratch their backs, and vertical feeding rails so that cows don’t bump their heads on horizontal railings when dipping in and out of the feeding trough. Cows are given between 0.5 and 0.8 metres crib space per cow to eat and stocked at a rate of 800 cows per hectare.

Grey’s management style of maximising cow comfort extends to his staff, where teamwork forms the foundation of a successfully run dairy. “We work hard, but we are a team. I wouldn’t want to be in any other industry,” says dairy manager Tatolo Mabuya. He is one of the 30 fulltime employees in the dairy, who are all focused on maintaining high standards.

Grey says that having good managers is vital to running a profitable dairy. “The ultimate aim is to have invisible cows – those that never get flagged for a problem, never require a vet. This can’t be achieved without attentive employees.”

For Mabuya, cow health starts with ensuring calves get the right amount of colostrum as quickly as possible after being born. He adds that good quality colostrum of at least 25 Brix is vital.

Mabuya aims to keep calf mortalities below 10% to ensure that 90% of calves born on the farm calve on the farm. “A calf that is sickly will never become a highly productive cow, so intensive management at the start is important.”

Managing the herd

The CowManager system has been used since 2018 to manage the herd. “But,” says Grey, “The data is only as good as the numbers that have been captured. So you have to be meticulous in recording everything, in real time.”

Since implementing the system, reproduction has increased since cows are more accurately flagged when on heat, sick or stressed.

For Grey and his team, dairy farming is “all about the cow”. A strategy with proven results, it bodes well for his ongoing expansion and animal welfare. Living in a society that places a big focus on the latter, Janvos Landgoed makes a positive case for increasing dairy consumption, and thereby the sustainability of the dairy industry.