Gut health and dysbiosis

Maintaining the balance of the gut flora is key to preventing dysbiosis. Preventing dysbiosis can improve poultry performance, health and welfare. It also can reduce the environmental impact of the poultry industry.

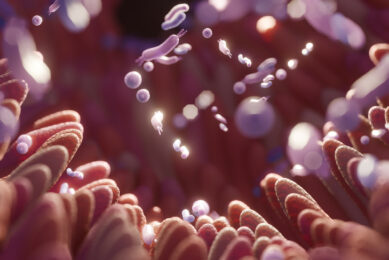

Normally, the small intestine contains few bacteria, but the large intestine and caeca contain billions of commensal bacteria (referred to as the intestinal microbiome). The microbiome significantly impacts gut health and contributes to the overall health status of the chicken host. The community’s primary function is to further digest and ferment feed, converting it to nutrients that can be absorbed by the intestines. However, the gut microbial community also performs immune system related functions. In newly hatched chicks, these bacteria stimulate intestinal tract development and educate the immune system. Once established, the microbial community functions as an immune defence system preventing colonisation of pathogenic bacteria by simply taking up space, creating intestinal wall barriers and producing antimicrobial peptides.

Recognising dysbiosis

There is a natural progression and change in the microbial community over time (presence, absence and prevalence). These changes occur in response to decreasing oxygen availability (aerobic respiration and organic compound oxidation), intestinal wall changes (crypt development and mucus secretion), feed and water ingestion, and environmental inputs (litter pecking). Significant disturbances, or dysbiosis, are abnormal microbial imbalances. Dysbiosis can lead to the overgrowth of some commensal members (e.g., E. coli and/or Clostridium spp.). When this happens, commensals can become opportunistic pathogens causing a gut immune response. Diarrhoea is usually the first sign as the host attempts to re-establish the balance. In severe cases, the mucosal cell layer of the gut wall lining can be penetrated by the opportunistic bacteria or their toxins causing enteritis.

Dysbiosis may be associated with litter that is wet and contains excess caecal contents. It is more predominant in countries that restrict antimicrobial growth promoters and therapeutic antimicrobial usage. The condition is seen mainly in rapidly growing broilers with good feed intake.

Poultry excrete urine and faeces simultaneously through the cloaca. In some cases, it is difficult to distinguish elevated urine output from increased faecal water loss or diarrhoea. Flushing, commonly referred to as an increased water excretion rate, is a normal physiological response to nutrition that induces water, electrolyte, pH, or osmotic imbalance. A relatively minor nutritional imbalance can induce an osmoregulatory disorder and flushing. It is important to be aware that flushing and dysbiosis may have similar symptoms.

The cost of dysbiosis

Although the microbiome is beneficial, the chicken still must keep this population in check through the production of antibodies and mucin secretions. During dysbiosis, the immune system must rapidly increase antibodies and mucin secretions to control bacterial population shifts. This requires diverting energy and protein production away from growth and maintenance and toward immune responses. Thus, a significant dysbiosis event can cause a reduction in final live weight and hence reduce producer profits.

Dysbiosis rarely impacts the entire flock. Thus, flock uniformity can suffer as afflicted birds experience stagnated growth while others continue to grow normally. Flock uniformity is a considerable factor in profitability as non-uniform flocks are more difficult to process and have downgrades.

Wet litter is an important consequence of dysbiosis-induced diarrhoea. The gut lining and undigested nutrients may be released in the excreta. Any mucus and undigested lipids in the excreta reduce the litter’s water holding capacity. Wet litter can cause multiple issues including foot pad problems (pododermatitis) and poor air quality that adversely impact flock health and welfare and, in turn, impact profitability.

Preventing, managing and diagnosing dysbiosis

Obtaining the chicks from a reliable source and attention to brooding management details (quality air, feed, water, temperature, and light) can promote the optimum development of a healthy gastrointestinal tract colonised by a stable microbiome.

Evaluating the drinking water with laboratory testing (at least twice yearly, particularly during the dry season) to ensure the quality meets the flock’s requirements can be helpful. Carefully choose feed enzymes and match them with local raw materials as enzymes impact substrates available for microbial fermentation. A good litter programme that includes reviewing the ventilation system and its capability to remove moisture from the litter is important.

Balanced diets play an important role in maintaining healthy intestinal microbiota. Poor-quality diets, putrefied animal protein, rancid fats, and anti-nutritional factors (toxins) can cause pathological changes by damaging the intestines or inducing dysbiosis. With dysbiosis, affected flocks will show signs of diarrhoea and increases in daily water intake. There are no specific post mortem lesions. The small intestine may have excessive fluid content, have excess caecal contents, often contain gas bubbles, and the rectum may be stained with wet faeces.

A definitive diagnosis of dysbiosis is challenging due to the non-specific nature of the symptoms; visualising intestinal lesions and a microscopic examination of intestinal wall scrapings (to exclude coccidiosis) can assist.

Success of antibiotic treatment is not guaranteed as there is no single taxa of bacteria appearing to be responsible for inducing dysbiosis. However, it is essential to eliminate other causes including coccidiosis, gut-associated viruses, or nutritional factors.

Several approaches practiced to control dysbiosis include:

- Apply a sound coccidiosis control programme

- Probiotics (competitive exclusion) and prebiotics may reduce the risk of dysbiosis

- Acidifiers (feed additives) have been reported to provide some benefit

Reducing the risk of dysbiosis

Given that the gut bacteria can be exposed to any ingested material, it is important to manage feed, water, and the house environment. Feed will be directly acted upon and used by the microbiome. Feed and ingredients testing and auditing suppliers can give valuable information when dysbiosis is suspected. Similarly, water and any water contaminants can directly benefit or negatively impact the microbiome. Finally, when the flock pecks at the litter, they ingest bacteria and fermentable materials. Keeping the litter dry will prevent bacterial overgrowth in the litter, which can reduce the risk of dysbiosis.

Author:

Hosam Amro, Senior Manager Technical Service Cobb Europe

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.