Feed in focus in the dairy net zero journey

A new collaboration between Trouw Nutrition and The Global Dairy Platform puts nutrition in the spotlight as a powerful tool to reduce carbon emissions from dairy farming.

The collaboration is set up as a task force within ‘Pathways to Dairy Net Zero (P2DNZ)’, a global and growing community, initiated by the Global Dairy Platform (GDP). The official kick off was done at a recent P2DNZ webinar, where speakers from Trouw Nutrition and the academic field delved into how animal nutrition can tackle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Reversing negative impacts

Javier Martìn-Tereso, Ph.D., Ruminant Research Center Manager at Trouw Nutrition kicked off the webinar by explaining that sustainable dairy farming entails a multitude of components, including lowering the environmental effect of dairy production, responsible use of natural resources, but also ensuring food safety- and security, optimising food chains, improving animal health and welfare, and more. He explained: “It is optimistic to see that in the last 60 years we have managed to increase overall food production a lot, with only a moderate increase in land use, hence leading to a reduction of emissions per unit of food by half. But the impact of dairy farming remains and keeps growing, and we must turn this around. The greatest opportunity for mitigation lies in optimising productivity and health. This can be partly done with genetics, but nutrition, feeding strategies and management decisions have a crucial role to play here.

Martìn-Tereso also addresses that the relevance and importance of ruminant methane emissions varies around the world. “In the EU and the US, we see that ruminant GHG contributes far less to the total national and global GHG levels, compared to Brazil and India. This can create a paradox, as methane mitigation is mostly needed in the areas where milk production is low, while these areas are also marked with low societal demand and economic means to work on emission reduction,” he said.

What to do, and where to start?

Today, there is a wealth of nutritional knowledge and novel tools that we can utilise in dairy to mitigate the emissions and increase overall efficiency. “An increasing number of dairy farmers are collecting environmental footprint data of their farming system, but still struggle how to use the data, and where to start making improvements on their farm”, explained Liz Homer, Ph.D., ECA Sustainability Manager at Trouw Nutrition in her talk. Homer addressed that it is important to look at all the different single decisions made (e.g., around calf rearing, feed ingredient use) at farm level and determine how each of them impacts efficiency, profitability, and the carbon footprint.

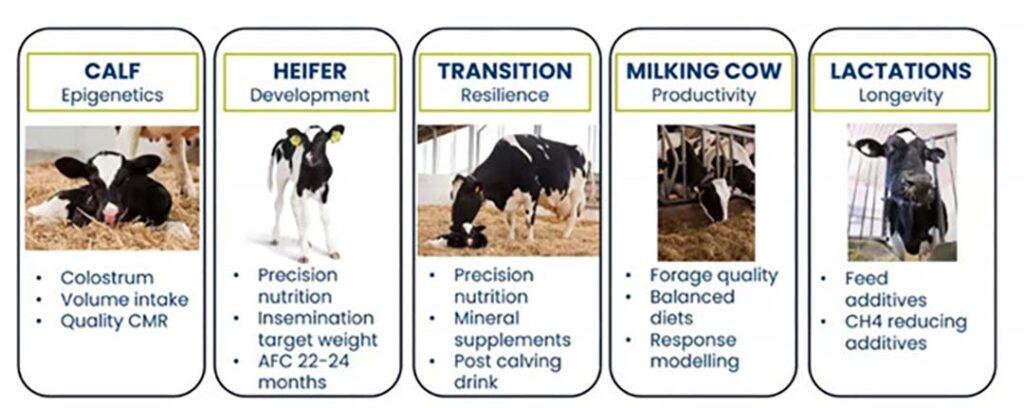

“If we look at what determines the carbon footprint of milk, we see that feed and enteric fermentation make up to 70-80% of the whole carbon footprint. This means that this percentage can be significantly reduced by dairy advisers and nutritionists, using the holistic tools we have today and critically look at all stages: from calf up to lactation number 5 (or beyond) and apply optimal nutrition and management practices (Figure 1). For example, every 100gr of average daily gain in the first 2 months of life can already lead to approximately 225kg extra milk in the first lactation, as shown by earlier research. Reducing the Age at First Calving (AFC) from 26 to 22 months can lead to a 6% reduction in carbon footprint. Also changes in sourcing of the raw material (e.g., soy or palm oil) can have a huge effect on the carbon footprint of milk. Farmers can challenge their feed supplier and advisor to plan short-, medium- and long-term measures that fit their specific farm goals and needs,” said Homer.

Figure 1 – Reducing carbon impact starts with tailor made support for each phase.

Activating our circular thinking

John Newbold, Ph.D., attached to Scotland’s Rural College explained in his presentation that the concept of ‘circular dairy systems’ can provide a good ‘umbrella’ for our thinking in how dairy systems will and should evolve in the future. Newbold further addressed that grass is by far the most important (and cheapest) feed that most cows consume. “This means that good utilisation of grass (ability to break down plant cells walls and passage rate in the rumen) by the cow is fundamental for high milk production, but also key to reduce the methane intensity levels,” Newbold explained. “We therefore must ensure that feed is always available but also digestible. The latter can be done through interventions such as forage processing, forage breeding, and the use of concentrates.”

Newbold addressed that the high generic merit cows of today (selected for high milk potential) are not always capable enough to sufficiently acquire nutrients from grass cell walls, negatively influencing methane emission levels. “High milk potential does not do always equal rumen potential to deal with high fibrous material. Potential solutions include the use of more non-grass forages such as alfalfa and clover, grass forages with a low content of cell walls, apply concentrate treatment and/or use of feed additives. For non-grazing systems (cow-led systems), we should also focus on maximising the use of co-products (promoting more circular thinking and dairy systems),” Newbold said.

Using new methane metric

According to methane and air quality expert Frank Mitloehner, Ph.D., from the University of California in the US, we should consider dairy as part of the solution and not the problem. Mitloehner addressed that some regions already made huge steps. “In my home state California, the dairy producers have managed to increase milk production by 60% between 1950 and 2018, reducing the carbon footprint of a glass of milk by two-third. Yet, we have ambitious goals to further reduce the emissions from ruminant production, especially methane. In his presentation, Mitloehner addressed that methane is a strong GHG, but also has a much shorter half-life in the atmosphere, compared to carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide (that will accumulate over time and stay in the environment).

Mitloehner: “We produce a lot of methane, but the good thing about methane is that it is also broken down. The net volume that remains still needs to be lowered for sure, but the commonly used metric to measure methane (GWP100) overestimates the warming impact of methane in constant herds by a factor 4 and overlooks its ability to induce cooling when methane emissions are reduced. This was also mentioned in the latest IPCC report (2021). Mitloehner mentioned that GWP* is a new (alternative) metric out of the University of Oxford that assesses how an emission of a shirt-lived greenhouse gas affects temperature. “This new metric not only accounts for methane’s short lifespan, but also its atmospheric removal and I hope we will see more use of this metric in the future, as this will give a more accurate picture.”

The new task force invites organisations in the dairy nutrition space to share ideas and solutions. Photo: Trouw Nutrition

Collaborate and join the journey

“In this webinar we touched on the impact we can have on the environmental footprint for milk,” JJ Degan, Ruminant Manager of Global Strategic Marketing, Trouw Nutrition addressed. Degan: “Each dairy system is different, but for each farm there are many opportunities to reduce carbon footprint through nutrition and feeding and increasing efficiency of the whole farm, from calf to cows that enter their fifth or sixth lactation cycle. We often know the potential, but not sure what the change and where to start. At Trouw Nutrition, we are committed to investing in improving the future of dairy farming. And to do so successfully, it is important that all stakeholders in the dairy chain cooperate in this mission. With this new task force and cooperation with the Global Dairy Platform’s Pathways to Dairy Net Zero initiative, we therefore invite other organisations in the dairy nutrition space to join us by focusing on opportunities to minimise the environmental impact of dairy production through innovative forage, feed and feeding developments and technologies,” Degan concluded.

If you like to participate in the P2DNZ Animal Nutrition working group, please sign up here. We are also excited to share that the first workshop with GDP will be held on April 22-24, 2024, in Leiden, the Netherlands. Save the date!

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.