US tariffs: How will farmers in Canada, the US and Mexico be affected?

US tariffs on milk products, grain and other imports – and reciprocal tariffs as well – are continuing to impact farmers in Canada, the US and Mexico, with no end in sight.

As of 4 March, US President Trump tariffed all Chinese imports at 10% (with a further 10% being discussed), and all Canadian and Mexican imports at 25% (except for 10% on Canadian energy). Steel and aluminum imports from other countries are subject to 25%. All other goods from all other nations will be tariffed starting in April at rates equal to those placed by each country on US imports.

Trump is wielding tariffs as a way to bring in additional revenue for the US (at the same time cuts to government spending are aimed at US$4 billion per day), stimulate domestic production of food, animal feed and other goods, equalise trading relationships and lower the value of the US dollar (making US goods exported to other countries more attractive). Trump has also explained that tariffs will be tied to US military protection and that he will introduce new types of Treasury bonds.

The tariff policies align with the views of economist Stephen Miran, who was previously not well known but was confirmed as head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers on 27 February. Miran goes into detail about these policies in a recent paper that has become required reading for those wishing to understand the rationales.

Retaliation fallout

In response to the US tariffs, Canada will be implementing 25% tariffs on a long list of American items, among them nearly 400 products in the sectors of dairy, grain (wheat, barley, rice), poultry, pork, fruit, vegetables and processed foods.

Mexico threatened retaliatory tariffs in early February but is now in negotiations. On 4 March, China imposed 10-15% levies against US agricultural goods, but increased this on 10 March. At that point, China slapped an additional 15% tariff on key American farm products, including soybeans, chicken, pork and beef.

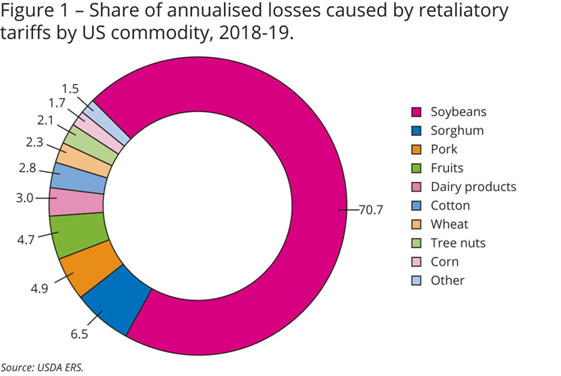

Reagan Tibbs, at University of Illinois Extension recently stated that retaliatory tariffs will likely cause “significant effects” on US farmers, who already have “precarious financial outlooks” for 2025. He notes that “the 2018-2019 trade war affected every sector of US agriculture, and a new trade war would likely have the same effect. A decrease in US exports to countries like China could further leave the door open for other countries like Brazil and Argentina to fill the gaps and overtake the US as major suppliers of agricultural products on the world stage.”

Regarding the greater US economy, Nigel Green (CEO of deVere Group, one of the world’s largest independent financial advisor-asset management groups) recently stated that these tariffs might be devastating because the US economy is already slowing. He notes that with Mexico, Canada and China being America’s top trading partners, a tariff war with them will increase costs on essential goods and further worsen the economic outlook.

Grain sector outlook

A recent outlook on how tariffs will affect grain markets was published by Jaime Luke, David Ortega and Molly Sears of the Department of Agricultural, Food & Resource Economics at Michigan State University. They first note that the US agricultural output “has grown faster than domestic demand for many products over the past 25 years, reaching US$174 billion in 2023. As a result, US producers have historically relied on export markets to sustain revenues in recent decades.”

Looking forward, these economists believe long-term tariff use will negatively affect US commodity-based farmers. Like Tibbs, they state “we saw a similar policy and result in 2018 when tariffs were imposed by the US on China. China was a principal buyer of US soybean exports when tariffs were imposed on Chinese goods. This resulted in China imposing retaliatory tariffs on US soybeans and other products. China then navigated the marketplace to seek alternative supplies of soybeans, mainly from Brazil and Argentina. During this period, US agricultural exports to China plummeted, with losses exceeding US$25 billion.”

With the tariff war underway, Luke, Ortega and Sears believe US producers now face “growing levels of uncertainty and volatility…at a time when producers have battled a multitude of challenges that have affected farm profitability.”

These challenges include high input prices from 2021 to 2023 on products like nitrogen and diesel fuel, due to supply chain issues and sanctions against Russia, with Russia being an exporter of large volumes of phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen fertilisers. However, Canada also exports large volumes of potassium in the form of about 7 million tonnes of potash annually to the US, much of it from Saskatchewan, which is about 80% of the potassium used to fertilise US crops. US farmers therefore may again have great challenges in sourcing low-cost fertiliser this year.

“In addition to high input prices, producers have seen major grain market revenue decline in terms of prices received for commodities,” note Luke, Ortega and Sears. “Producers are not receiving premium prices for commodities like they did in 2022 to 2023. The higher prices received for commodities like corn in these years helped balance out the increased input costs mentioned previously. However, commodity spot prices in 2024 markets were significantly lower than in previous years.”

Meanwhile, last week China announced tariffs on Canadian grains and other food products that total about CAD$2.6 billion in annual trade, retaliating against (and matching) tariffs that Canada introduced in October 2024 on China-made electric vehicles, and steel and aluminium products. The tariffs are scheduled to take effect on 20 March, and include a 100% tariff on Chinese imports of both Canadian canola and peas, and 25% on pork products.

Dairy

As with grain, retaliatory tariffs by Mexico and other countries would hurt the US dairy industry. About 20% of total US annual milk production is exported in the form of liquid and powdered milk and other products. Indeed, because Mexico imports so much US non-fat dry milk, it was not listed in early February in Mexico’s potential list of items that may be subjected to retaliatory tariffs.

However, there has already been a chilling effect on non-fat dry milk and skim milk powder market prospects, as recently stated by US-based Daily Dairy Report analyst Sarina Sharp. The situation was positive in these markets towards the end of 2024, with low US output, tight global stockpiles and a steep decline in milk and milk powder production in China making greater Chinese imports and higher prices likely.”

Non-fat dry milk prices did indeed reach a 2-year high in November 2024. However, with the tariff situation, Sharp describes Mexican demand for US milk powder as “subdued”, with buyers expressing concerns about committing to buy milk powder that could face tariffs in the near future.

However, the US Dairy Export Council announced on 7 March that the total value of US dairy product exports increased in January to reach 20% over 2024, which is a record. While DFM and skim milk powder were only up 0.4% year over year, US cheese exports were up in January for the 13th month in a row, 22% over the January before. This cheese went to Mexico (the biggest customer) at basically the same rate as always, but shipments to other countries such as Japan and South Korea reached very high levels, 59% and 34%, respectively, over the year before. Central American and Caribbean shipments were also up.

US butterfat exports also went up a huge amount in January, with total shipments growing 145% year over year. The Council states that “butter exports were 41% (+927 mt) larger than last January, recording strong gains across the globe but especially to Canada (+19%, +300 mt), Central America and the Caribbean (+103%, +211 mt), and the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) (+776%, +204 mt).”

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.