Achieving top-quality silage ahead of harvesting maize

There is a continued desire to increase the share of silage in the diet for dairy cows as it is mostly ‘homegrown’ and hence presents a way of controlling costs in dairy production. However, the amount that can be included in the diet depends on the quality of the silage.

Many important steps need to be considered to ensure high-quality silage, and with corn being a mostly ‘one-per-season-crop’, attention to detail during silage-making really pays off as what you get is what you have to feed for the next 9-12 months.

Below are some important considerations, none of which should be ignored as they are all interlinked.

Safety

Agriculture ranks among the most hazardous industries. Unfortunately, there are still many injuries related to silage, not least during harvesting, which requires big machines in operation and large volumes of forage to be harvested, stored and compacted in a very short and intensive time. However, every serious injury or fatality during the ensiling process could have been prevented! So, stay alert!

Decision-making

Identify the decision-makers and empower them to make the right decision in a timely manner. This includes the authority to slow down the field team if compaction is not keeping up. Oxygen is the enemy, and nothing can really compensate for poor compaction.

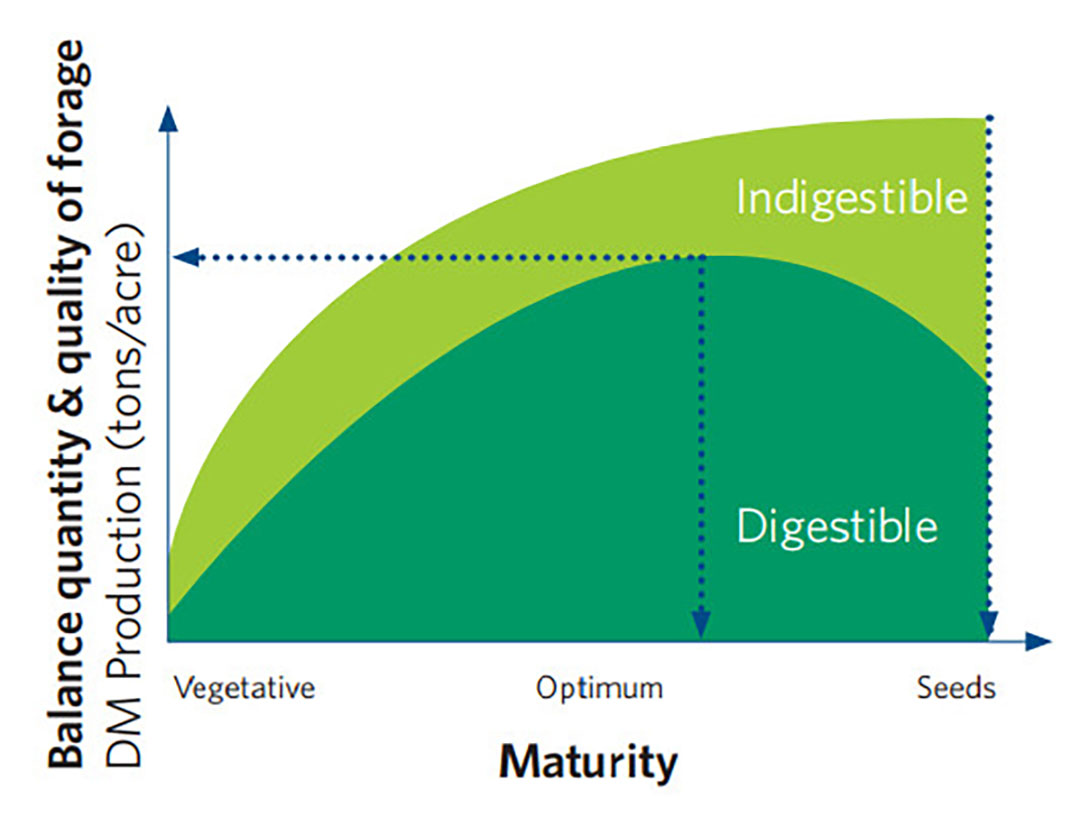

Maturity

Maturity reflects the antagonism between quantity (yield) and quality (digestibility). Remember, you are not making silage to store and ferment but to feed your herd. Forage digestibility is the ultimate link to milk production.

Dry matter

With the increasing size of operations, forage harvesting takes time. This means that you will likely begin harvest when the crop is perhaps a little too moist and – equally likely – finish when the crop is perhaps a little too dry. At both ends of the dry matter content, challenges emerge, and being aware of this will help you mitigate these challenges.

Hitting target moisture is critical for reducing the risk of undesirable fermentation, minimising effluent, and achieving optimal density.

Chop length

Chop length for silage affects compaction and fermentation in the silo, as well as the level of effective fibre in the diet. A dryer crop requires a shorter particle size. Do not rely merely on the settings of the machines, but check the output at the spout. Direct the changes to the field team if the chop length is not optimal. Ensure there are no uncracked kernels. Kernel processing correlates to the availability of starch to rumen and intestinal digestion. Research demonstrates that each 1% decrease in faecal starch results in 0.33 kg more milk.

Compaction

Oxygen is the enemy! Match forage delivery rate to packing tractor weight to exceed ‘the rule of 400’ (packing tractor weight kg = 400 x tonnes of forage delivered/hour). Bring the forage into the bunker in thin (10-20 cm) layers and synchronise the time spent harvesting with the packing time. If the harvester works 10 hours, your packing tractor should pack the forage 10 hours/day. In situations of, for example, high dry matter, increase compaction time by 20%. If the compaction team cannot keep up, slow down the field team – your silage will thank you for it!

Oxygen is the enemy! Match forage delivery rate to packing tractor weight to exceed ‘the rule of 400’ (packing tractor weight kg = 400 x tonnes of forage delivered/hour). Bring the forage into the bunker in thin (10-20 cm) layers and synchronise the time spent harvesting with the packing time. If the harvester works 10 hours, your packing tractor should pack the forage 10 hours/day. In situations of, for example, high dry matter, increase compaction time by 20%. If the compaction team cannot keep up, slow down the field team – your silage will thank you for it!

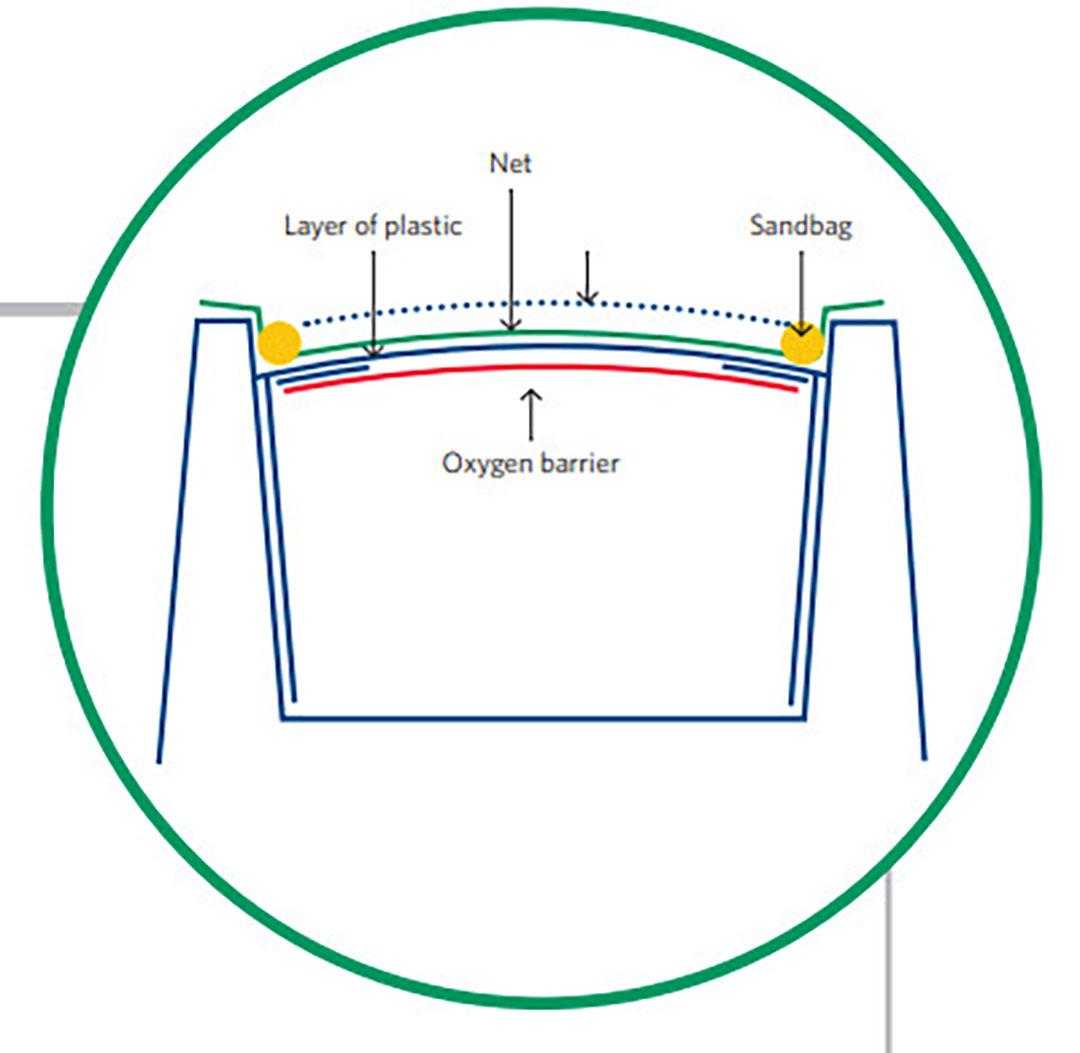

Sealing

Cover quickly! If you come to a stop overnight or due to a rain shower, pull a sheet of plastic onto the bunker. Note that 10 mm of rain will change DM in the top layer by 1%. Consider a good-quality oxygen barrier film. Ensure protection against birds – a recyclable fleece-type of protection has become available that could be considered a good alternative or addition to bird nets. Add weights uniformly (tires should touch each other), and place gravel bags at walls and at the ends. Inspect and repair holes with plastic tape.

And a few words on fermentation control…

General experience shows that spontaneous fermentation of the forage will take place as soon as anaerobic conditions are established. However, the results will not always be consistent. The main reason is that even if compaction and sealing are executed with perfection, 30% or more of the total silage volume is made up of air. The presence of oxygen will inherently allow undesirable microorganisms to grow and metabolise nutrients that should otherwise be utilised by the natural flora of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to drive the fermentation.

To mitigate this dilemma, turning to LAB-based silage inoculants that can scavenge the oxygen and create an oxygen-free environment in less than 24 hours is an obvious option. SiloSolve FC with Oxycap Technology from Chr Hansen offers just that. And, as an added benefit, makes it possible to start feeding new silage after one week of storage instead of the 2-3 months usually required…