Bluetongue: EFSA reviews control measures

Eradication of bluetongue is very difficult and mass vaccination, followed by sensitive surveillance systems, will work best according to EFSA.

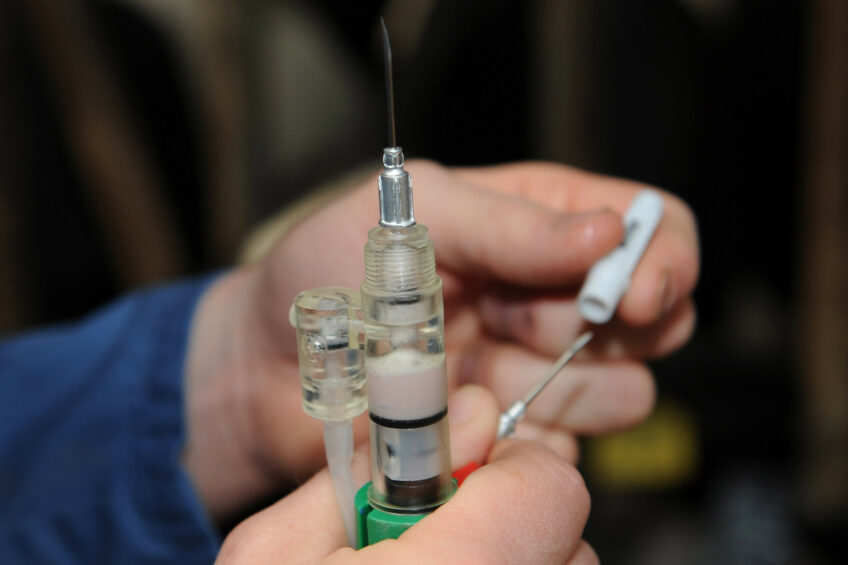

Bluetongue is a vector-borne viral disease of domestic and wild ruminants such as sheep, goats, cattle and deer. It is transmitted through the bites of certain species of Culicoides midges.

Over the past 15 years, bluetongue outbreaks (of a variety of serotypes) have occurred across Europe. In a new EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) opinion, it is stated that the incidences of the disease during the last 15 years have not only included unexpected epidemics in areas where it had not appeared for more than 10 years (e.g. BTV-4 in the mainland of the Balkan Peninsula in 2014) but also low-impact circulation of certain serotypes, some of them of unclear origin, incursions of new serotypes, vaccine incidents and disease resurgence (BTV-8 in France in 2015) raising concerns and evidencing new challenges.

Review of control measures

The affected countries sometimes used diverse control policies. This is why EFSA’s experts from the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare have reviewed control measures for bluetongue and options for safe trade of animals from infected to free areas, following a request from the European Commission. They have also updated their scientific advice on epidemiological aspects of the disease, particularly its transmission patterns. EFSA experts conclude that eradication of bluetongue is very difficult and at least five consecutive years of vaccination covering 95% of susceptible cattle and sheep would be needed, followed by sensitive surveillance systems capable of detecting low levels of virus prevalence – lower than 1% of animals in a monitored area. The disease could otherwise re-appear some years after completion of the vaccination campaign. Surveillance systems should be defined on a case-by-case basis taking into account aspects such as the geographical area monitored and the epidemiological phase of the disease.

Immunisation and transmission

Experts also highlighted in the scientific opinion that new-born animals receive antibodies from their mothers that protect them from the disease for about three months. However, these antibodies may interfere with vaccination, thus making vaccination ineffective during this period. Another important factor to keep in mind is that some species of the midges that transmit the disease are active throughout the year – especially in mild-winter areas such as the Mediterranean basin. In these areas, transmission of the virus may occur at any time. In colder areas, such as in northern Europe, midges are inactive for about three winter months, during which transmission is halted.

Further steps

The scientific opinion will assist policy-makers as they review legislation on bluetongue. In line with this, EFSA will classify different types of bluetongue according to their characteristics by the end of June 2017. This will help identify specific protection and control measures.

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.