Happily exchanging one dairy farm for another in Germany

Theodor and Petra ter Veen exchanged their farm with 140 cows for a future-proof company with many opportunities, and a small additional payment. Despite miscalculating the additional costs, 4 years later, their business is on track and they aim to grow further.

It is freezing and the flat land around Leer in northern Germany is covered in snow at the beginning of January. Leer is an ideal area for dairy farmers: almost exclusively grassland on clay.

“At our old location, 15 km to the north, we couldn’t expand,” says Theodor ter Veen. “There we had 78 hectares, 60 of which were leased. We were in a water extraction area, right next to the village. We had 140 dairy cows on 2 milking robots in a stable with 85 stalls. Weather permitting, the cows were outside. The young cattle were on a second farm with 75 hectares where my parents lived. The buildings were listed, so new construction was not allowed there. When my father died suddenly in 2018, we ran into labour problems and started thinking about the future.”

The regional government then asked whether they would be willing to sell their land for nature development and buffer zones and this served as a catalyst. That future actually had only 1 option: dairy cattle elsewhere, in a location with opportunities for growth, and preferably not too far away.

“We‘re dairy farmers through and through and we probably have a successor,” Theodor explains his line of thinking. A company with fairly new stables and 100 hectares in one block near Emden was the first to come into the picture. “That picture was a good fit, because I grew up in that area,” says Petra. Before they could say “yes” that company was grabbed by a livestock farmer who had been bought out for urban expansion.

Theodor then heard from a rural property agent that a company in the area was being discretely sold. “Despite the inadequate information, I could deduce from the description that it had to be this company. I knew the owner and contacted him directly.”

This ultimately resulted in an exchange with an additional payment, supervised by a broker.

Much too tight a budget

Ter Veen surrendered 75 hectares and a farm with listed buildings and in exchange received a company with a permit for 300 dairy cows, 120 young cattle, slot silos and 6,500 cubic metres of manure storage. Negotiations started in 2018 and were postponed to 2019.

“We did make mistakes,” Theodor admits. Funding was kept very tight. Besides the additional payment of €100,000 for quality differences between the companies and €30,000 for feed supplies, more than €100,000 also needed to be financed. That was not nearly enough to cover the extra costs.

“First of all, we hadn’t budgeted for cleaning and disinfection costs, that cost us 60 grand,” says Theodor. At the new location there was a side-by-side milking parlour. Ter Veen took his 2 Lely A4 milking robots with him and wanted to add an A5. Space was immediately created for a fourth robot, because the goal is to ultimately milk around 260 cows. “Lely indicated that it would like to supply the extra A5, but that extra investment of €110,000 hadn’t been taken into account either.”

The costs of much-needed adjustments to the stables were also underestimated, and they had to deal with a major outbreak of Mortellaro disease. “At our old business the cows and young cattle had grazing almost all year round due to overstocking. We trimmed them once or twice a year and occasionally when problems arise,” he said, adding that 4 months after the move, the problems started. “With almost continuous trimming and driving the cows through the foot bath every week, we now have it under control. But it cost us about 60 cows, plus a lot of lost milk money.”

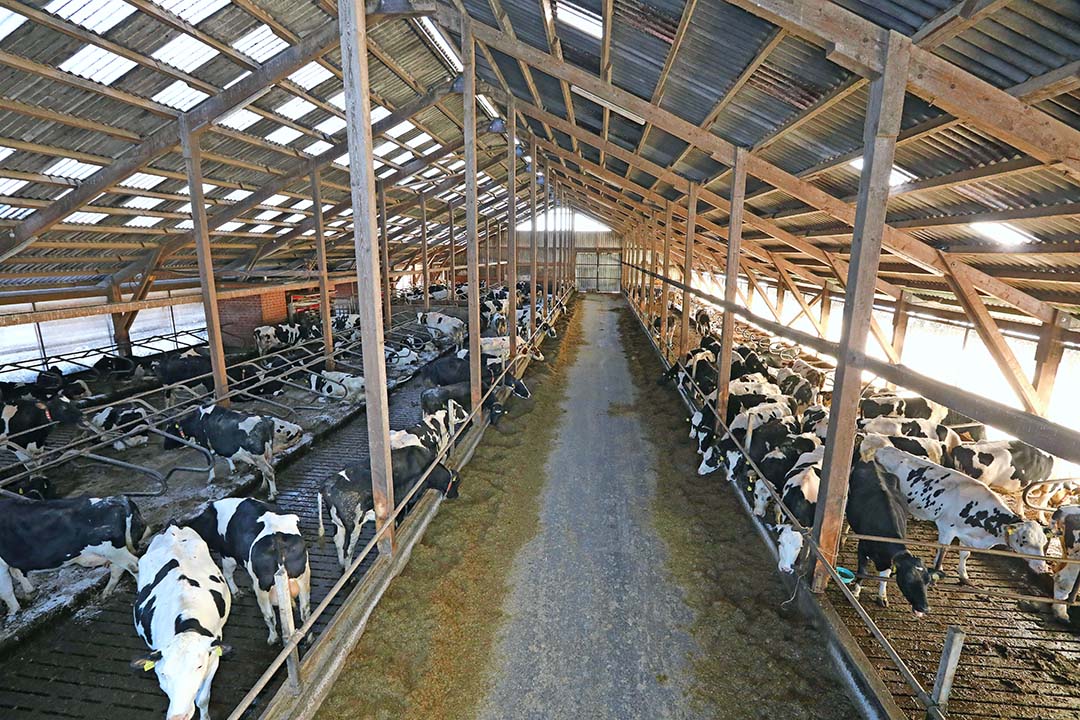

Due to the accelerated removal of cows, the stables are now only two-thirds full. The large number of young cattle retained proved to be just enough to maintain our livestock population. There are 285 cubicles in the 2 stables, with some straw cages on top for cows about to calve. Effectively, we now have 190 cows in milk. There are many cows nearing the end of their lactation cycle.

“We don’t inseminate until production is below 40 kg per day. Inseminating earlier will put too much strain on the animals. The cows are consistent, production levels are high. As a result, we receive 6 cents per kg above the basic price from Ammerland, our milk cooperative.”

Buying cows

Theodor ter Veen mentioned he had assumed that he could expand to 250 cows from his own breeding. He did not want to purchase animals because of health risks. “That’s no longer feasible. We are now looking for a group of 50 cows that are used to robots. We can’t find that in Germany. There are hardly any companies here with robots that are closing down. We asked if he would like to purchase livestock from a Dutch farmer stopping. Well, it will have to be paid from the current account, which is already around the maximum. Total funding is €1.6 million on 78 hectares of property, stables, supplies and livestock.”

This financing must be repaid within 20 years, and the interest rate is fixed for another 8 years at approximately 2.7%. This means bank charges are around €125,000 per year. Then additional financing for direct money-generating cows should be a no brainer, right? It is not that simple, Petra indicates. “According to the bank, we could easily have financed half a million more with the exchange in 2019. We largely paid for the setbacks and overruns from our own resources. Now the bank is making things difficult, not just for us, but for many dairy farmers. In the first 2 years we were forced to shift our payroll and feed bills. These are our largest costs, together approximately € 27,500 per month. Thanks to the last 2 good years in financial terms, we‘ve managed to catch up with this.”

It is easy – and according to Theodor, not costly – to purchase roughage in the nearby area. Besides extra labour, the 50 additional cows mainly require concentrates. Ter Veen does not carry raw materials: “Mainly because it takes too much extra time to load those loose raw materials into the TMR ration. Concentrate feed based on corn grain is much easier.”

Based on the current feed costs for 190 cows with young cattle, the additional feed costs for 50 cows will be approximately €5,000 per month, and other variable costs a maximum of €5,000. The extra milk money from 50 cows would amount to €18,000 per month. “Don’t forget the extra labour costs required, at least €3,000. We now spend €5,000 per month for our permanent employee who works 30 hours a week and the casual employee who does all the maintenance in an average of 10 hours a week. I can manage the company alone for a few weeks during holiday periods, but that would not be feasible with 240 cows.”

He could opt for a trainee; Theodor has the necessary papers for this. “You‘re then very dependent on who you‘re offered. And even then, the trick is to bind this person to you, in practice they leave after 1 or 2 years. Our permanent employee joined us after the takeover, he’s been working here for 40 years and knows the company inside and out.”

Labour is a major bottleneck

To reduce the amount of labour required, almost all agricultural work has been outsourced to the contractor. Theodor spreads fertiliser and weeds the grass. In the autumn, the employee empties all the wells including the old slurry tank. The contractor takes care of all other matters, which costs approximately €120,000 per year or 7 cents per kg of milk. On top of that, there are hardly any mechanisation costs, other than some maintenance and fuel. This is limited to one cent per kg of milk for the self-propelled feed mixer and the 2 tractors that have almost been written off.

Feeding takes up a lot of time. The self-propelled feed mixer runs 2 hours a day to produce 4 TMR rations for the animals. Distributing and pushing the feed with the mini loader also takes another hour per day.

“We want to move to an automatic feeding system with storage bunkers. Then you can cut blocks in stock, so you are not bound by fixed times. An unskilled employee could do that job. Such a switch will save a lot of labour and labour is now the main bottleneck at this company.”

All roughage is stored in slot silos, the TMR for dairy cattle is a mix of the first, second and third cuts of grass, supplemented with maize silage and concentrates.

Grazing requires additional acreage

Pasture grazing is also high on the wish list. “We have always enjoyed that; it’s good for the cows’ leg work and Ammerland, our milk cooperative, pays extra, on top of the €75 per cow that the EU pays as a subsidy for outdoor grazing,” says Theodor. However, in the current farm layout, there is too little land directly accessible from the stables – 2 roads cut through the plots. “In a milking parlour you can quickly transfer the animals twice a day, which is manageable. We work with milking robots; those roads are too restrictive for that.”

Ter Veen is therefore keeping an eye out for additional acreage in the area. At €600 per hectare for grassland, the rent would be easy to cover from the 50 extra cows and lower costs for purchasing roughage. “It also fits well in manure sales. We‘re now at 173 kgs of nitrogen from animal manure per hectare; on average we can go up to 175 kgs on our current acreage. We don’t have to put down manure yet. If we keep those 50 extra cows, we will have to dispose of about 1,300 cubic metres of manure per year. With additional land, this cost will be eliminated. If leased land with buildings comes up for sale, we can sell our old location with 18 hectares to finance the purchase.”