Danish dairy farmer doubles milk production

Danish dairy farmer Jesper Olsen is not afraid to take the next steps. The 60 cows he had in 2007 have now grown in numbers to 360, and there will be over 500 next year. The acreage has grown from 160 ha to 360 ha, 35 ha of which are leased. Milk production per cow more than doubled in that time frame.

“My father was not a real cow man, but he did do many things well. Most importantly, he kept a close eye on costs, made a profit every year and invested those profits in land purchases. That is the basis for where I am now,” said Olsen.

It was clear that Jesper would become a farmer after agricultural school. “I only had 9 years of school in total,” he says. To make this possible, his father built a new barn for 230 dairy cows in 2007. In 2009, Jesper bought half the company and focused mainly on dairy, particularly on increasing production – at first, without staff.

In 2011, an acquaintance asked if he had any work for him. “I also wanted to have a weekend off. After some thinking and calculations, I came to the conclusion that I could afford it and I hired him. That ultimately changed my whole idea of labour and work. I suddenly had time free to take a good look at the company, tackle issues and improve the results. That worked out very well; it made me much more of an entrepreneur.”

After the first employee, Olsen got the hang of it and more came. Now there are 4 permanent employees: a Danish herd manager, a Romanian, a Ukrainian and a Danish practitioner. “Coincidentally, there has been a lot of turnover in staff in recent years. I now employ many new people, but they usually work for me for 3-5 years.”

This rapid change in staff is noticeable in the results. Milk quality deteriorated at the end of 2021, with the somatic cell count increasing from 140,000 to 198,000. “I had to check the milking routines with my herd manager,” he said. The cell count is now almost back to its old level.

Not going for milking robots

In 2014, the former cowshed was demolished and a new barn was built for the heifers and dry cows. This created room for the current 360 cows. A permit for further expansion of another 150 cubicles was granted at the end of 2021. This extension of the 2+3-row barn from 2007 will be realised in 2024. “After the permit was issued, construction costs increased, partly due to the crisis in Ukraine. I decided to wait. This paid off; the price of building materials has fallen sharply and is now almost at pre-Ukraine levels,” said Olsen.

The Dane estimates the construction costs at approximately €600,000. He will cover this from liquid assets. “We have never earned as much as in 2022 and we have invested a little extra.” he said.

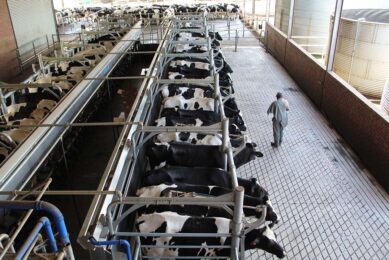

For the impending expansion, one option on the table was to switch from the 2×12 rapid exit milking parlour to milking robots, in several variants. But Olsen will keep milking in the parlour. The purchase price of milking robots did not play a role. “The price was okay,” says the entrepreneur. “But our milking parlour is up to date and modern. It can last another 10 years without investments.”

Investing in 2 or 3 robots just for the group of high-producing cows was also not possible. “I work with staff and want to keep the systems as simple as possible. Then you shouldn’t go to two clearly different systems,” he noted.

Labour provision plays no role in the choice of the milking system. According to Jesper, personnel are easy to attract in the region. “And if necessary, you pay 10% extra. Milking is unskilled labour, as is feeding. If you switch to robots, you need knowledge workers. Those are especially difficult to attract. That is why we prefer not to destroy capital, continue to work with simple systems and if necessary just add one extra person to the payroll.”

Also from a purely financial perspective, the choice made to continue this way is the best, Jensen says. “We calculate 3 cents/kg of milk higher costs for robots, partly due to capital destruction, but mainly due to having to attract more expensive labour. That is easily €150,000 per year for 500 cows.”

Low feed costs

If you look at the company’s figures (see Table), Olsen scores around the average compared to similar companies in many areas. But there are really significant differences on 2 points: the cost of feed purchases and the mechanisation plus labour costs. The cost of purchasing feed remained at 10.7 cents/kg milk in 2022. The average of the Danish European Dairy Farmers (EDF) farms was 4.5 cents higher. “We achieve these low costs in 2 ways. Firstly, a good yield of grass and corn. Grass cultivation here is simple: we mow 80 ha in one go, 4 times a year. A contractor forages the silage.”

A second cost-reducing factor is the joint purchase of feedstuffs and business supplies with a group of 60 dairy farmers. They employ 2 traders who monitor all markets. Olsen indicates in advance how much he needs for a year: “It takes a lot of work off my hands and relieves me of worries. The traders follow the markets better than I ever could. Over the years it has resulted in at least 1 to 2 cents/kg of milk in savings on purchasing costs. Not that they are never wrong; things once went terribly wrong with non-GMO soy. But you also sometimes decide too quickly or too late.” He now follows market developments just to maintain a feel for them.

The grass is fertilised with digestate from a cooperative biogas plant that collects the fresh slurry once a week and pays Olsen €4.30/m3. Olsen receives digestate free of charge back – he has 9,000 m3 of storage space for this. “It’s very beneficial, because the nitrogen in the digestate works much better than that in the liquid manure.” Spreading the digestate on the grassland is the responsibility of the dairy farmer.

Little labour and cheap mechanisation

The costs of mechanisation, labour and contract work in 2022 were 12.3 cents/kg of milk, or 3.8 cents lower than the average on Danish EDF farms. The costs of paid labour are almost 40% lower at 3.6 cents/kg of milk. Olsen only needs 24 hours per cow compared to 30 in Danish EDF farms. The labour provided by family members is calculated at 1.5 cents/kg of milk compared to 1 cent/kg on the average Danish EDF farm. “Despite his retirement, my father still works a lot of hours, especially on the tractor.”

This tractor work is mainly arable. In addition to 130 ha of silage maize, 80 ha of grass and 20 ha of fallow, there are 130 ha of arable crops. Of this, 70 ha are wheat and barley, 30 ha rapeseed and 30 ha rye on the worst land. “The soil here is not the best anyway; it is very sensitive to drought. That is why we also use rotation: 3 years of grass, a year of corn and then a year of grains.”

The Dane can only irrigate the 100 ha surrounding the farm buildings. The other large plots, mostly purchased after 2010, are located some distance away. “We usually buy plots of 20 ha to 40 ha,” he noted.

The Dane has invested little in mechanisation. “We bought a new tractor last year, which was only 7 years old. The other tractors are all around 20 years old. They can still do what I want – that’s the most important thing – which is a lot of work for little money. And we do the maintenance ourselves.” That also ensures low costs. Despite the age of the tractors, maintenance only costs Olsen 1.2 cents/kg of milk. That’s half a cent less than average.

Low cash cost, high profit

The 2 significant pluses in feed costs – labour and mechanisation – lead to a benefit of 8.3 cents/kg of milk. There are no real negatives at this company. In 2022, costs were 28.0 cents/kg of milk and a breakeven price (including income supplements) of 29.8 cents. On average they were 38.3 and 35.7 cents on the Danish EDF farms. And those benefits are not a once-off. In 2021, Olsen’s cash cost were 27.6 cents and the breakeven point was 28.5 cents. In 2021, they were barely 2 cents below that.

Added to the sales prices (64.9 cents total in 2022, 47.7 cents in 2021), it is clear that good money is being made on this Danish farm. The margin was 32.9 cents/kg of milk in 2022 and 16.3 cents in 2021. If you multiply that by more than 4 million litres of shipped milk, it is clear where the cash for the stable expansion comes from. Although, land is also purchased every year. “The goal is 10 to 20 hectares,” says Olsen. With an average land price in South Jutland that is creeping towards €20,000 per ha again, this amounts to an average investment of €300,000 each year.

These investments will become more difficult, the Dane estimates. The interest he pays a credit cooperative is mainly variable. It was around 0% for a long time, but rose to 2.9% in 2022 and is now at 4.5%. That is an additional cost of about €200,000 per year. “That margin is available. But you have to take it into account again. I now have to consider the steps better, I never want to get into trouble.”

It is uncertain what the next step will be after the upcoming expansion. The company can grow towards 800 dairy cows, but then the rearing of young stock will have to take place elsewhere. “I expect that after the expansion we will mainly grow in arable farming. I won’t really have to choose until one of the children – in about 10 years’ time – indicates that they have a preference for dairy. Such a growth step can still be taken and then there will already be enough land in the company for the expansion.”