Texas region: “Most dairies have had it. We haven’t seen the last of HPAI”

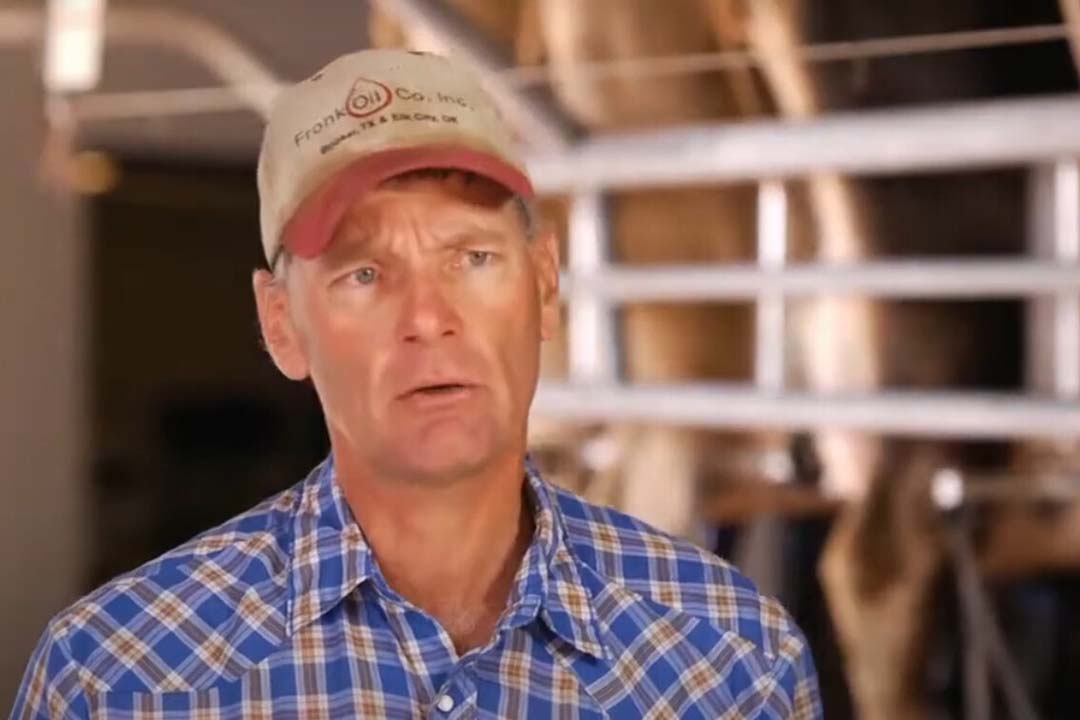

Sieto Mellema in Dalhart in the northwestern tip of Texas saw reduced intakes and a mild fever in the cows on his farm in early March. Ultimately, 10% of the cows became ill due to what turned out to be an infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), also known as bird flu.

“There were no mortalities, and two-thirds of the affected cows were back to normal within 14 days with production at the original level,” says the farmer who emigrated from Groningen to Texas with his parents in 1979. “A group of cows dried up. It was striking that the disease only affected second-calf and older cows. All the other animals – first calf cows, youngstock, our beef cows and the cross-bred calves on our farm or at the feedlots that we have under contract – remained healthy.”

How much milk did you miss?

“Across the entire herd, an average of 1.5kg of milk per day for 3 weeks. That is a total loss of approximately 170,000 kgs of milk. That loss was on top of the poor milk price we had during that period.”

Did you treat the animals?

“We didn’t know what it was. The diagnosis of HPAI was only made after the symptoms had disappeared and the cows had recovered. We separated the cows with symptoms and gave them plenty of fluids, electrolytes and probiotics. You know that once something goes wrong in dairy cattle, more will follow, hence those preventive treatments. It worked, and we are back to normal. The cell count rose towards 250,000 at the time and is now below 150,000 again.”

Did it spread to humans?

“No. Luckily not. None of us or our employees were ill during that period.”

Were you the only dairy farmer with problems?

“No, almost every dairy farmer in the wider region has experienced the same problems with their dairy cows. In that respect, the contamination figures that USDA publishes are a significant underestimate of reality.”

Did you notice any other things?

“Yes. We saw that the disease struck first and most clearly on farms with cross ventilation barns. These are farms with relatively little volume per cow, as reported by a virologist. In retrospect, it started happening there at the end of November 2023. On farms where the cows are kept outdoors, the disease struck months later and more mildly. Although milk is pointed out as a source of infection for the animals, it seems to me more like an airborne contamination and from birds. The virus goes from dairy farm to dairy farm, without animal contacts. From what I hear, the number of affected dairies is now slowing; the weather cooperates. It is now becoming drier and warmer, which also slowed the spread of the virus.”

Your beef cows are often older animals. Do you see anything in the beef cows?

“No, we didn’t see anything abnormal there and we haven’t seen anything yet. The calving season started 2 months ago. No problem at all among the animals, even though they are in contact with the dairy cows. The crossbred calves in the feedlots, the finishing farms, also show no abnormalities. Only the older dairy cows became ill. I am not saying that the other animals and animal groups were not infected, but that we saw nothing. My gut feeling is that they must have been infected. Only large-scale testing can now prove that. The cows showed no clinical signs, so it’s not an easy task, given the circumstances.”

You see similarities with the situation in poultry. Are you concerned about reinfection in the coming fall and winter?

“I do expect the disease to return, in some form. According to veterinarians, mutations can easily arise. My biggest concern is that it will spread to humans. We all realise that we have probably not seen the end of all this yet.”

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.