Factors affecting cow response to mastitis treatment

Failure of mastitis treatment is a common problem in clinical practice due to interference of other factors that can affect the reliability of successful treatment. Treating cases with a better understanding of these factors will minimise the risk of treatment failure and at least helps in knowing why a particular treatment works well in one situation but not in another.

Mastitis is one of the most prevalent and costly diseases of dairy cows worldwide. The disease is commonly treated with antimicrobial products containing amoxicillin, penicillin, cephalosporin etc. We look at factors that play a role in affecting treatment.

Animal factors

1. Breed

Friesian cows are more prone to infection and less responsive to mastitis treatment compared to the lower producing dairy breeds when kept under the same farming conditions. The difference here is probably due to genetic factors such as the greater systemic inflammatory response postpartum, the lower immunoglobulin and other immune-related proteins in colostrum, and the lower leukocyte cell components in Friesian cows.

2. Age

Older cattle have a poorer response to treatment as compared to younger cattle. In one study, there was a reduction in clinical and bacteriological cure rates from 91% (lactation 1) to 47% for older cattle (lactation 4). A reduction in chronic symptoms (changes in the milk, gland, or inflammatory response) was also markedly greater in cows in the first lactation as compared to older cattle.

3. Cow’s general condition

Sick or dehydrated cattle are prone to have reduced circulation. This can affect the normal course of systemic distribution of drugs and the rate of elimination thereof. Illness can thus result in a prolonged duration of detectable levels of the drugs in tissue and milk.

4. History of infection

Cows with a history of previous cases of clinical mastitis are less likely to respond to treatment, probably because of the changes that occur within the udder, resulting in weakened vascularisation and consequently, impaired drug distribution. In a study including 143 cases of clinical mastitis, cows treated for the first time in the current lactation were 7 times more likely to result in a bacteriological cure and 11 times less likely to have a recurrence as compared to cows that had experienced a previous case in that lactation.

Mammary gland factors

Some factors related to the mammary gland itself can be the reason for mastitis treatment failure. Commonly listed factors include:

1. Teat canal infections

Standard methods of intra-mammary antimicrobial administration into a mastitis quarter or as dry cow therapy do not necessarily eliminate teat canal infections. The mastitis-causing organisms (MCOs) are harbored in the teat canal and serve as a potential reservoir for later infection of the parenchyma of the mammary gland. After dispensing antimicrobial therapy into the gland, the resident teat canal infection may then facilitate a new, super-infection, or be a source for re-infection.

2. Udder tissue necrosis

Necrosis of the affected area of the gland and abscess formation may obstruct the diffusion of antimicrobials to some extent, by compression or blockage of the milk duct system. The diffusion of antimicrobial products throughout the gland is thereby impaired. For this reason, it is often very difficult to ensure that antimicrobials have good contact with MCOs, particularly when administered via the intra-mammary route. It has been proposed that systemic administration of antimicrobials may overcome these problems.

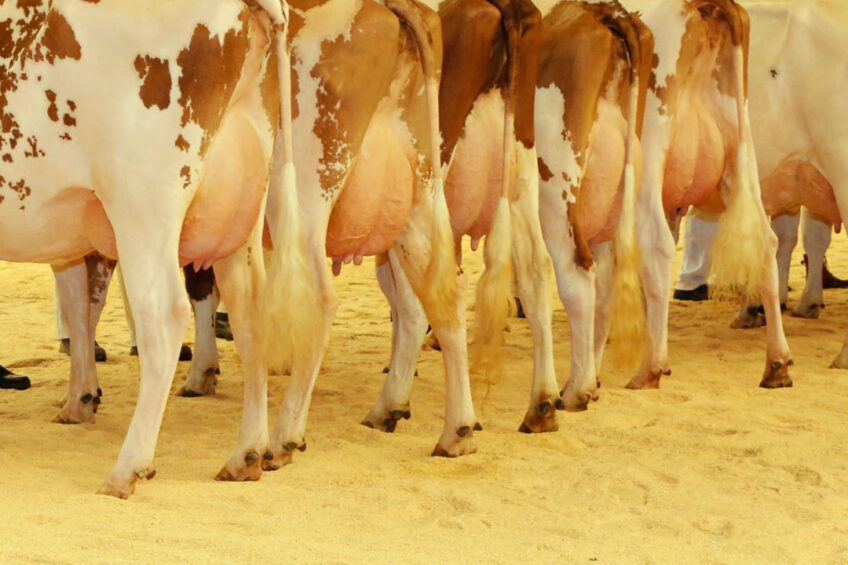

3. The number of quarters infected

With more infected quarters, there is a lower chance of cure at the cow and quarter level. If not all quarters of a cow are treated, the uninfected quarters of that animal are at higher risk of re-infection with the pathogen, probably as a result of auto-reinfection; that is, reinfection of cured quarters by non-cured ones within the same cow. Quarter location is also a key factor, with hindquarters showing significantly lower cure rates. Generally, hindquarters have higher infection risks due to their larger volume relative to front quarters, which makes it a factor affecting treatment.

Nutritional factors

Nutrition has a direct impact on immune function and susceptibility to mastitis and may indirectly increase cow susceptibility to mastitis through its impact on other diseases. Some nutrients can induce one or more metabolic diseases when either deficient or in excess in the transition diet. Milk fever, for example, has been shown to slow the closure of the teat sphincter thereby making the udder more prone to microbial invasion and less responsive to treatment. Cows with milk fever are 8.1 times more likely to have mastitis and 9 times more likely to have coliform mastitis as a result. Mastitis is also associated with ketosis and retained placenta, and fatty infiltration of the liver is slower in clearing E. coli from the mammary gland of the cow. Much of these disease problems can be alleviated through proper nutrition and management strategies which, in turn, help the control and treatment of mastitis.

Environmental factors

Many microorganisms have been isolated from cases of mastitis and are associated with the cow’s environment. Common environmental pathogens include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and environmental streptococci such as S. uberis and S. dysgalactiae. Cows are primarily exposed to these pathogens between milking times when teat ends come in contact with contaminated bedding, manure, contaminated water, or soil.

Tips for controlling environmental mastitis and facilitating the disease treatment of cows kept indoors or on pastures:

- Cows should not be kept in damp, filthy conditions.

- Adequate, clean, dry bedding is essential and should be replaced daily.

- Overcrowding should be avoided, particularly in straw yards.

- Overgrazing and overstocking should be avoided.

- Shade areas (around trees) should be large enough to avoid excessive contamination thereof.

- In wet conditions, cows should be kept in well-drained paddocks.

Drug and treatment factors include:

- Low bio-availability.

- Inadequate local tissue concentration.

- Weak or excessive passage of drug across the blood-milk barrier.

- A high degree of milk and serum protein binding.

- Improper antimicrobial selection.

- Antagonism between concurrently used antimicrobials.

- The short half-life of the drug.

- Side effects of the drug.

- The tolerance and high resistance to a given antimicrobial, the case in which the use of a different drug should be considered.

- Improper dose and route of administration, depth of insertion of infusion cannula, and duration of treatment.

- Inadequate supportive treatment with anti-inflammatories which decrease swelling and provide better distribution of the drug.

- Inaccurate diagnosis and delayed initial treatment.

References are available from the author upon request.

Join 13,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the dairy sector, two times a week.