Debunking a myth: ‘You can’t successfully import foreign cattle breeds into Africa’

When Arla Foods decided to build a 500-cow dairy farm in Nigeria, I always wanted to go with foreign breeds as the local breeds are not proper dairy breeds. But every time I mentioned this to local people here in Nigeria, and also elsewhere, almost everyone urged us to not go that route.

The history of importing cattle to West Africa was bad, almost frightening. Stories about imported cows that died like flies are known all over the area, and this has almost stopped the development of the dairy industry.

Many have not succeeded

But are the stories true? Well, as far as I know, yes, most of them are. Imported animals have quite often died shortly after arriving in Africa – not only in Nigeria but also in other countries. This track record made me look closely into matters as our operation relies on imports. Most in the industry know that there are some serious cattle diseases in Africa, but with our knowledge today, I was surprised to learn about the many failures with imported cattle.

I quickly found out what the main issue was when it came to previous failures. By far, in most cases, the management was the main cause or, more accurately, the lack of proper management. In many cases, these high-producing animals with an unstimulated immune system had been brought into Africa and then treated like they were local cattle. The local cattle can survive in the hot environment, without access to water and food for extremely long periods, and they have a strong immune system that manages to fight many diseases.

In almost all the cases I read about and/or heard about, the management was not optimal. It can hardly come as a surprise that a Holstein cow would for sure have a tough time if she was not vaccinated against the most common diseases, kept in unshaded areas at 30-40°C and without access to feed or water for long periods.

Focus on biosecurity

Knowing about the history of cattle imports into Africa and learning from the failures, it was crucial for us to take the right steps, and by right steps I mean figure out how we should take heifers into the country and how to take good care of them.

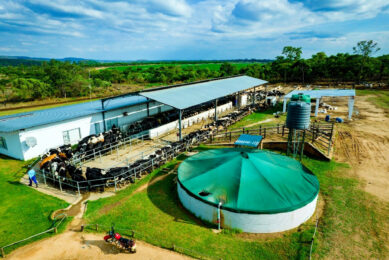

First of all, we designed the farm with strong biosecurity in mind. All vehicles entering the site should be disinfected and all those working with or who are in close proximity to the animals have to shower on the way to work and change into farm clothes. Furthermore, the housing facility for the animals was equipped with cooling fans, insulated roofs and wide spaces to make replacement of the air around the animals as good as possible. Then all sleeping areas – both boxes and cubicles – were covered with dry, soft sand, a known material in which bacteria has a hard time thriving. All this was done with possible diseases and animal welfare in mind.

The right leadership

The second thing was to hire a veterinarian with experience in vaccination and disease control. To have a veterinarian on the farm was essential to successfully establish protocol around vaccination against the most known diseases. This was crucial for the future of the operation.

Strong vaccination programme

The key to success is certainly to have a strong vaccination programme, as in Africa there are still many challenging difficult cattle diseases that were either eradicated a long time ago in Europe, or are under control. Thankfully, there are good vaccines available and we use them frequently to continue increasing the possibility to run our operation as successfully as possible.

And what is it we vaccinate against? We vaccinate against Foot and Mouth Disease, Lumpy Skin Disease, Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia, Black Quarter Disease and Hemorrhagic Septicemia. This has, of course, come at a cost, but any saved animal is worth so much more, so for us this is a no-brainer.

Where are we today?

Well, we imported 215 heifers in May of 2023. About a third was pregnant at the time. The rest of the imported young heifers became pregnant here. Now, 18 months later, we have, of course, lost some animals due to different things, but mainly due to things that dairy farmers would call a ‘normal’ reason for exit.

When it comes to challenging diseases, we have experienced our share despite the vaccinations, but the clinical symptoms have been milder than expected and we assume this is because of our vaccination programme. Now, we are close to 400 animals on the ground and in 2 years’ time we expect to have filled up the farm with the planned 500 cows plus youngstock.