Deep learning for efficient dairy farming

CattleEye is on a mission to create the world’s first autonomous livestock monitoring platform. CEO and co-founder Terry Canning tells us more.

As the world population grows and the demand for livestock protein increases, farmers are trying to find new ways to up their production. Sustainable dairy farming, however, is not just a matter of farming more animals to meet the rising demand. With legislation limiting emissions from livestock, the future of dairy farming lies in increasing efficiency rather than expansion.

Terry Canning, co-founder and CEO of CattleEye, understands these challenges like no other. Canning tells Dairy Global more about his company and its mission to create the world’s first autonomous livestock monitoring platform.

A repeat entrepreneur, Canning grew up on a dairy farm in County Armagh (Northern Ireland), studied engineering and spent 9 years working in telecommunications and cloud computing. In 2004, Canning applied his knowledge of cloud computing to the livestock industry and founded FarmWizard, which grew out to manage about 4 million cattle. After selling FarmWizard to the Wheatsheaf group in 2015 and exiting the company completely in March of 2019, Canning decided to take a new approach to livestock monitoring: “My previous business allowed people to record information about livestock by using apps, so if you wanted to record movement or record the animal, it was always reported by humans,” Canning explains. “What I want to do with CattleEye is to provide a way to do this automatically so that the farmer doesn’t have to be involved.” CattleEye uses video analytics powered by deep learning artificial intelligence to deliver insights to farmers.

Making use of the latest developments

CattleEye’s technology makes use of the latest developments in the industry. “The computing power and the type of tools that enable machine vision to work correctly have now become available. Tools such as Amazon Webservice, and better cloud computing capability allow us to develop artificial intelligence that can make use of video analytics and derive specific insights from those,” Canning continues. CattleEye took off when Canning came across co-founder Adam Askew, who had spent 12 years working with the same kind of technology in cancer detection. Once Canning and Askew had founded CattleEye, they raised about €1 million in investments and were joined by Askew’s team, made up of 6 people that were working on this technology, which had just been acquired by Philips. “Once we were up and running, we started with a very small farm of just 90 cows and used lots of cameras, which were ‘learning’ how to work. Now, we’re monitoring 11,000 cows,” Canning adds.

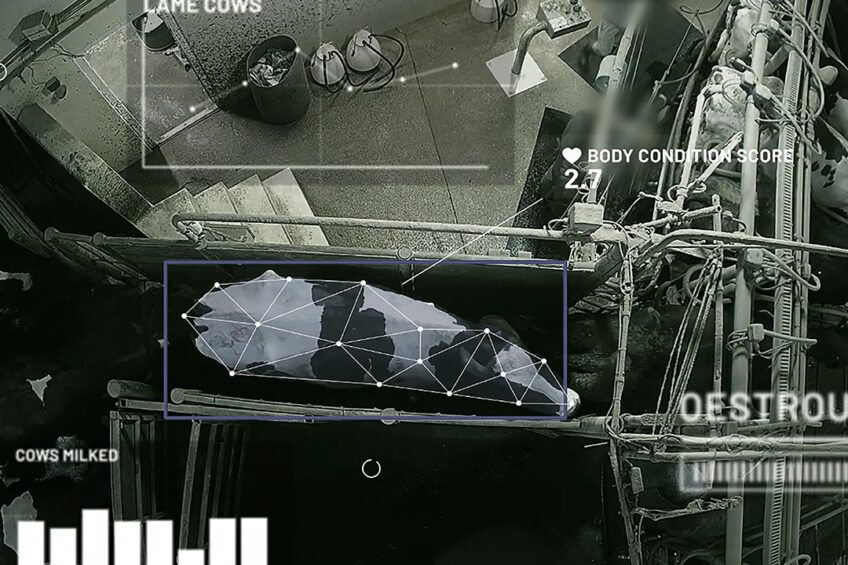

“Between that, we initially did some work with the University of Liverpool, we brought on another farm in Dorset, and we just brought on our first farm in the US last month,” Canning says, and goes on to explain how CattleEye’s technology uses artificial intelligence where farmers would previously have used their own eyes: “We are recording lots of videos and putting in expert scores – done by vets who go to the farms to score the cows – which we then use to train our neural networks. These networks can look at a video of a cow, extract data, identify it, and offer insights on factors such as mobility scoring and body condition scoring.

“If we take mobility scoring, for example, the AI can use the video to identify lame cows early on. The farmer can put in a threshold score between 0 and 100, with 0 being the best and 100 being the worst. If a cow scores over the threshold, an alert is created, which is then sent to the farmer’s mobile phone or to their farm software system,” Canning explains. “They would then get a foot trimmer or a vet to look at the cow and fix the cow’s feet.”

Using simple security cameras

The technology behind CattleEye is far from simplistic, but getting the technology up and running on a farm is not a complicated task: “Due to the coronavirus, it was difficult to go and visit some of the pilot farms, but what we did discover was that the farmers could easily put up the cameras themselves. Maybe this was, in some ways, a good thing because this demonstrated the ease with which the system could be installed. The farmers could go to Amazon, buy the cameras, and install it themselves,” says Canning. “We are unique in that we are using simple security cameras instead of specific hardware which then needs to be installed in the barn. We use a €120 security camera, advise the farmer where to place it, and then the camera connects to the cloud. The AI then starts to learn, to find the cows, and to derive insights about them which are then delivered to the farmer.”

CattleEye conducted its first pilot on Canning’s father’s farm to learn about some of the problems dairy farmers face. Since then, the company’s pilots have expanded, including but not limited to a pilot at a research farm in Dorset of 5000 cows. In addition, Tesco, the UK’s largest retailer, have been engaged with CattleEye for the past 12 months: “Tesco currently requires their dairy farmers to mobility score on a regular basis, but this takes the farmer a long time and it is sometimes difficult for the farmer to be consistent in the scoring, so they were very attracted to the idea of doing the scoring automatically,” Canning explains. As a next step, the University of Liverpool will validate the company’s technology and trial it in 3 farms. Canning: “Our plan is to run a pilot in January with the functionality being widely available in April of next year.”

Farm report, Ireland: Balancing farm and family

Farm report, Ireland: Balancing farm and family

Dairy farm succession can be a touchy subject among families and usually involves a son taking over the operational duties from his father.

As well as running pilots in the UK, CattleEye is running a pilot in the US and is planning for more pilots by January of next year, potentially also in South America. “We want to learn more about the cow,” says Canning. “Today, we are focused on current insights, and we think AI will give us other insights about the cow that we don’t even know about yet. We’ll gather data, and this will then allow us to correlate other insights that may improve the health and welfare of the dairy cow.

Canning concludes by saying: “The brilliant thing about AI is that it continues to learn; we teach it one thing and then it gets better and better, finding insights that we haven’t thought of yet. We expect that data will lead us in new and exciting directions.”

For more information, visit www.cattleeye.com